www.stateofthecoast.scot

Saltmarsh Introduction

Key Findings

Saltmarsh landscapes (Fig. 1) are common to Scotland. They are found in the intertidal zone (where the sea rises and falls between over the course of a day), in areas sheltered from the worst of the waves (NatureScot, 2023). They grow from the gentle settling of sediments into mud substrate, forming patches of vegetation separated by streams of water (Scottish Seabird Centre, n.d.). Their soils are waterlogged due to the frequent input of seawater, often resulting in the formation of peat (National Ocean Service, 2024). Saltmarshes are the mid to higher latitude equivalent of mangroves, which form in similar intertidal environments of the tropical latitudes (Davidson-Arnott, 2009).

In terms of biodiversity, saltmarshes are incredibly important environments. They are the spawning grounds for many economically important fish species, and support communities of unique plants, small mammals, invertebrates, and resident and migratory populations of birds (Scottish Seabird Centre, n.d.; The Wildlife Trusts, n.d.).

Not only are these environments ecologically important, but they also provide direct benefits to the human population. Their sediments can trap contaminants and improve water quality, while their complex structures are excellent flood defences (Fig. 2) (Hudson, Kenworthy & Best, 2021).

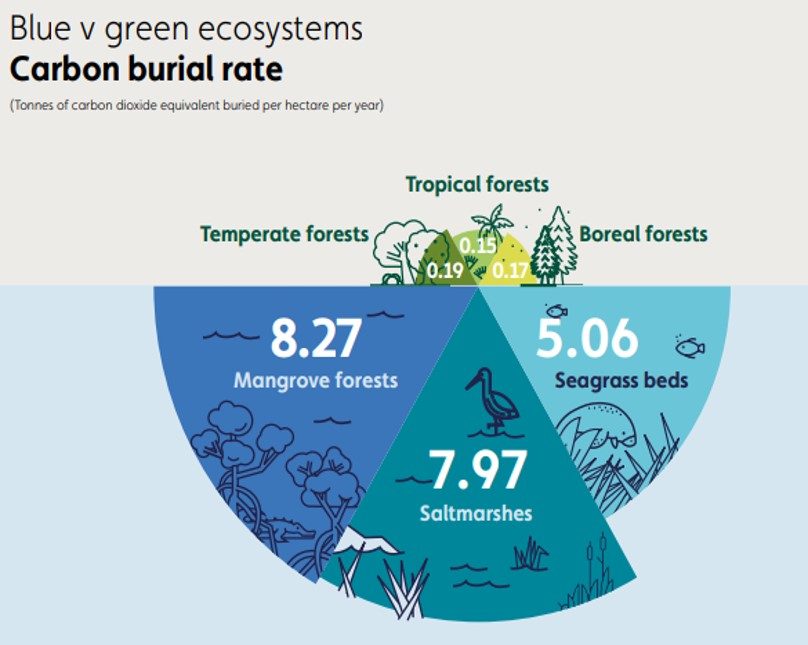

They are also a significantly important component in the fight against climate change (Hudson, Kenworthy & Best, 2021). Due to the anaerobic soil (lacking in oxygen), carbon that becomes incorporated into the soil via plant photosynthesis decays very slowly, potentially being stored for millenia if undisturbed (NOAA, n.d.). When stored in this coastal/marine enviornment, the carbon is known as ‘blue carbon’. Saltmarsh carbon burial is one of the most efficient natural methods of carbon sequestration (Fig. 3), better than both seagrass and forests (Hudson, Kenworthy & Best, 2021). This also means the loss of saltmarsh landscape is highly damaging – releasing the long-buried carbon back into the atmosphere and contributing to planetary warming.

Figure 1: Saltmarsh (Venables, 2010)

Figure 2: A comparison of traditional seawall coastal defences, compared to natural systems in managing extreme conditions: the friction of the complex wetland and reef structures lessens the intensity of the waves (Temmerman et al, 2013).

Figure 3: Comparison of terrestrial and marine natural carbon sequestration methods – saltmarshes are responsible for the 2nd largest share of hectares buried per year (Fewins, 2023).

Notes

Linked Information Sheets

Key sources of Information

Davidson-Arnott (2009) Saltmarshes and mangroves

Fewins (2023) Wetlands for Carbon Storage

Hudson, Kenworthy, and Best (2021) Saltmarsh Restoration Handbook- UK and Ireland

National Ocean Service (2024) What is a salt marsh?

NOAA (n.d.) Coastal Blue Carbon

Scottish Seabird Centre (n.d.) Salt Marshes

Temerman et al (2013) Ecosystem-based coastal defence in the face of global change

The Wildlife Trusts (n.d.) Where to see saltmarshes and estuaries

Reviewed on/by

Status

Live - next update 20/08/2026

To report errors, highlight new data, or discuss alternative interpretations, please complete the form below and we will aim to respond to you within 28 days

Contact us

Telephone: 07971149117

E-mail: ian.hay@stateofthecoast.scot

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.